The humidity system in our humidors

• The humidity system we use has a manufacturer’s warranty of 1 year. (We tested the unit for more than 3 years without any problems.)

• Hands-free reliable operation

• Built-in filtration & mold retardant

• Automatically set to maintain humidity at 70%

• User adjustable humidity from 60-80%

• Built-in integral humidity indicator

• Battery or outlet powered

• Standard adapter included: 120VAC (optional 240VAC available)

• The water cartridge should be replaced every 6 months (life expectancy of sponge): Cost: ~$15+shipping. ( You can order this part through us by sending us an email with your request)

• Refill water tank with distilled water only when dry (every 3- 4 weeks, depending on the time of year and the amount of cigars).

Biedermeier

Biedermeier refers to works of literature, music, the visual arts and furniture in the period between the years 1815 (Vienna Congress), the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and 1848, the year of the European revolutions, and contrasts with the Romantic era. It was the age of the Austrian Chancellor Metternich, Prince Metternich, whose diplomacy and influence dominated much of the post-Napoleonic period. It was a period of conservative politics in reaction to the horrors and chaos of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s far-reaching conquests. Liberalism and popular movements were viewed negatively, and thus suppressed; it was the heyday of the secret police. But it was also a time of great creativity. Great names like Beethoven, Schubert, Johann Strauss the Elder and Joseph Lanner dominated the Viennese music scene. Despite censorship, theatre and literature flourished. It saw growing industrialization and the resulting migration from rural to largely urban life. It was also the beginning of the Railway Age in almost all European countries. The Biedermeier period came to an end in the revolutions of 1848. At the same time the so-called Metternich System of conservative and diplomatic conferences with the major powers to try to maintain order by acting concertedly in Europe, also came to an end. The term “Biedermeier” applied initially only in a joking spirit. It is believed to have been named for the worthy, bourgeois-minded "Papa Biedermeier," a humorous character featured in a series of verses by Ludwig Eichrodt, published in Fliegende Blätter.

The Biedermeier period found expression in comfortable, homelike furnishings, simple in design and inexpensive in material, fitting the requirements of the people in a time of little wealth following the Napoleonic Wars. Biedermeier designs were simplified forms of the French Empire and Directoire styles and of some 18th-century English styles, and were often elegant in their utilitarian simplicity. Vienna was in many ways a spiritual and artistic center, strong enough to blend the most varied impulses into its own synthesis. Already in the production of Empire-style furniture, the Vienna furniture builders had found their definitive expression. Their more cherished and fantasy-filled designs differed clearly from those of French taste and the latter's German derivatives. Viennese furniture makers worked securely and solidly, which is reflected in the charming home furnishings of the artisans' best quality. Austrian furniture is lighter and designed for livability, elegance and private life. Viennese Biedermeier furniture can be especially recognized in its relationship to and partial transition from Empire style, and it shows itself in striking, artistically mature products of high quality. In 1816 there were 875 independent master cabinetmakers in Vienna , in 1823 already 951. Some ran genuine factories; the best-known and most influential of them was Josef Danhauser, who was already employing 100 workers in 1808. Danhauser sold not only furniture in his factory, but also home furnishings such as drapes, carpets, clocks and even glassware. The Viennese Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) has over 2500 of Danhauser's catalogue drawings. They show the never-ending fantasy and decors. Nowadays Biedermeier has become very popular due to its timeless design. Its high functionality and simple forms suit today's modern sense of living.

Conservation

Conservation is the preservation of cultural property for the future—it is not the restoring of that property. “Restoration” improves the appearance of a work of art; “conservation” maintains the present appearance/condition of the piece as is.

French polish

French polishing is a wood finishing technique (and not a substance, as commonly assumed) for wooden furniture that results in a very high gloss, deep color and hard surface. It consists of applying many thin coats of shellac using a rubbing pad. The rubbing pad is made up of wadding inside a square piece of cotton and is referred to as a fad.

The process is lengthy and very repetitive. The finish is obtained through a specific combination of different rubbing motions (generally circles and figure-eights), waiting for considerable time, building up layers of polish and then spiriting off any streaks left in the surface.

The 'fad' is commonly lubricated with an oil which is integrated into the overall finish. This helps to prevent the 'fad' from lifting previously applied layers of shellac. Which particular oil is used greatly influences the overall finish. Typically, "softer" oils, such as mineral oil, will produce a glossier and less durable finish whereas "harder" oils, such as walnut oil, will produce a more durable finish.

In the Victorian era, French polishing was commonly used on mahogany and other expensive woods, and was considered to give the best possible finish to exclusive furniture, but was very labor intensive and many major manufacturers abandoned the technique around 1930, instead preferring the cheaper and quicker techniques of spray finishing nitrocellulose lacquer and abrasive buffing. Another reason it fell from favor is its tendency to melt under low heat; for example, hot cups can leave marks on it.

Humidity

We recommend keeping the humidity level of your home always above 30%. This is especially important in cold weather—particularly the first sub-zero day of the season—as the humidity can drop dramatically from 30% to 10 or 15%, which may cause cracks in furniture. Most of our clients use a humidity system integrated in their central heating, but individual humidifiers positioned in a main living area are an acceptable alternative.

If you use a humidifier in your home, it is important to set it up before cold weather comes, as the change in humidity levels between summer and winter can be detrimental to your furniture. Wood, as a living material, is able to absorb and lose water, causing it to expand and contract according to outside temperatures (which affect the humidity inside your home). It is due to this risk of expanding/contracting that you must keep the humidity indoors at a constant level.

Intarsia

Intarsia is a form of wood inlaying that is similar to marquetry. The technique of intarsia inlays sections of wood (at times with contrasting ivory or bone) within the solid matrix; by contrast marquetry assembles a pattern out of veneers upon the base structure. The technique of intarsia is believed to have been developed in the Islamic world; introduced into Europe through Sicily, the art was perfected in Sienna and in northern Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, spreading to German centers and introduced into London by Flemish craftsmen in the later sixteenth century. After about 1620, marquetry tended to supplant intarsia in urbane work.

Marquetry

Marquetry is the craft of covering a base structure with veneer, forming decorative patterns, designs or pictures. The result may be furniture, decorated small objects, or free-standing pictures. Marquetry differs from the more ancient craft of inlay, in which a solid body of one material is cut out to receive sections of another material. The veneer used is primarily wood, but may include bone or ivory, turtle-shell (conventionally called "tortoiseshell"), mother-of-pearl or pewter, brass and fine metals. Marquetry using colored straw was a specialty of some European spa resorts from the end of the 18th century. Many exotic woods as well as common European varieties could be employed. The simplest kind of marquetry uses only two sheets of veneer, which are temporarily glued together and cut with a fine saw, producing two contrasting panels of identical design, (in French called partie and contre-partie, "part" and "counterpart"). Simple geometric marquetry designs reminiscent of basketwork, tiling or trelliswork, are often called 'parquetry,' in reference to the similar patterning of parquet flooring. Marquetry as a modern craft is most commonly knife-cut: the knife used is therefore of paramount importance. Other requirements are a pattern of some kind, some cheap (i.e. not very sticky) clear sticky tape, PVA glue and a base-board. Finishing the piece will require sand-paper or wire wool, possibly with a sanding block. Either ordinary varnish or the techniques of French polish can be used to seal the piece.

The technique of veneered marquetry had its inspiration in 16th century Florence (and at Naples). Marquetry elaborated upon Florentine techniques of inlaying solid marble slabs with designs formed of fitted marbles, jaspers and semi-precious stones. This work, called opere di commessi, is commonly known as pietra dura. In Florence, the Chapel of the Medici at San Lorenzo is completely covered in a colored marble facing using this demanding jigsaw-like technique.

Restoration

Restoration is a process that attempts to renew the original beauty of a work of art.

Sawcut Veneer

In the 18th century, veneers were largely manually produced, and during the 19th century, the trend shifted toward specially developed sawing machines. In the beginning of the 20th century, however, our modern method of veneer production—i.e., blade technology—was developed, and it replaced older methods. Although this new technology afforded furniture makers cheaper products and more efficient production in general, the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the new method had a price: older methods produced a much more stable, high-quality veneer, and this quality was deeply compromised in modern veneer production.

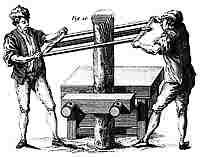

The veneers that we use are produced with an authentic veneer saw in accordance with the horizontal reciprocating principle dating from 1888: they are produced by one of only two remaining companies in the world to use traditional technology, and are thus of the highest quality possible. Aside from the saw being powered by electricity rather than by water, the production process has not changed at all for the past few centuries. The company from whom we buy our veneers even produce the blades themselves, which is indispensable for production of high quality veneer. Saw blades similar to those used 100 years ago are produced by cutting, whetting and setting the teeth made from metal blanks. In order to get the most veneer pieces out of a single tree trunk, thus minimizing waste, the trunk is glued onto planks and then clamped onto the veneer saw.

|